We’ve written articles and made videos that discuss the issues with defect-led thinking. People being trained to only find what is wrong with trees. It makes sense to understand certain features of concern. But by identifying those features and only those features, it appears to the public that we do whatever we can to justify tree removal. There are ways to reduce the risks associated with most features, but we’ve somehow found it easier to convince clients their trees are dangerous instead of valuable. That they need to be removed instead of managed.

That’s what their competitors do, and that’s just part of the game. Nobody really cares about keeping trees in “good health”, that’s just the PR AI-written stuff on our websites.

We’ve made it a point in our practice, and we’ve published on this principle before, that you don’t need to do tree removals to have a successful tree company. But that requires a different skillset and a different mindset from the status quo.

Arborists within that status quo can have a preservation skillset, but it demands them to assess their money making skills in a different way. In a way that doesn’t look too kindly on the premise of making a living on removing a community's trees. A career based on killing things, on removing habitat, especially when working with trees is easier, less expensive, and less destructive.

At the same time, there are many arborists we’ve spoken to that lack a sense of fulfillment in their work. Some carry out work they know is either detrimental to the tree, or the whole “if i don’t do it someone else will” excuse.

I could apply a similar argument to preserving trees and informing your clients. “If I don’t do this, nobody else will”. If I don’t give this client the good information, nobody else will. If I don’t stand up for this tree, nobody else will.

A lot of arborists at tree companies don’t have agency to do that. That defies the orders of the company they work for, mutated by a combination of influences that results in a fundamental mistrust of our industry.

“The market demands tree removal.” Maybe sometimes. It is the only thing most tree guys offer, and that has taught the market to demand it. Not the other way around. They’ve been taught how to identify reasons to remove, not reasons to retain.

Our culture teaches that tidy equals health and that beauty equals safety, treating trees as decor. Many arborists, influenced by these same biases, guide the public towards that intolerance of nature. That if trees are not perfect, they are dangerous and ought to be killed.

Business incentives reinforce the pattern. Debt and payroll and profit margins reward production. The more we scale, the more we must cut, and the faster we must do it. This is our industry’s legacy.

Manufacturers and trade organizations sell us on bigger machines and faster removals, distracting us from learning about ecology. From how to communicate risk. From how to actually assess tree stability. From answering the public’s real demands.

Add to all that a lack of ethical oversight and consumer protection, and the result is public mistrust. People sense the contradiction between our words and our actions. We tell them we’re caretakers of trees, but everything about our behavior and practices says otherwise.

The mistrust isn’t unfair; it’s earned.

Too Much Tree Killin’

“Are you taking it down?” is the first question a passerby asks a tree crew while they set up at a job 9 times out of 10. All arborists or tree guys across the spectrum know this question. Why might that be?

The tree care industry has certainly earned that reputation from the public. That we just cut and kill trees. We can’t really begrudge the public for always asking us that. Does taking “care” of trees mean we take them out back behind the shed? That is meant to be funny, but… That is kind of what our industry does.

Lots of tree guys and tree companies spec into the tree removal stuff. They see their competitors getting big chippers, big lifts, tree meks, they see it on instagram, they believe all the hype and the tree industry dogma. That’s what they see at trade shows, advertisements in magazines. That’s what all signs point to. “This is the direction your tree company should grow towards”. Or as my friend Scott Geddes put it “this is what the market demands”.

They think that’s what tree work is. They don’t know that the market thinks it is getting professional guidance from so-called ‘tree experts’. When you actually start to converse with clients in depth, asking probing questions, explaining the possible outcomes of their requests, you realize very quickly there is most certainly a market demand that is not being met.

Who would you rather be? The guy who takes care of trees? Or the guy that kills nature for a living? Sure, one gets more instagram likes, but once you’ve learned a bit more about tree stability and risk, see the big picture, putting all of your stats into tree-killing doesn’t seem like a great way for a long and fulfilling career with a good reputation. You’ll spend your time making your community worse if all you do is kill trees.

This constant question of “are you taking it down” is the greatest representation of a public that fundamentally mistrusts us.

Well-Deserved Public Mistrust

Where’s the mistrust originating from? Many different forces act on the public that leads them to be suspicious of us. And we certainly have done our part to deserve that. Other forces are a bit more nebulous.

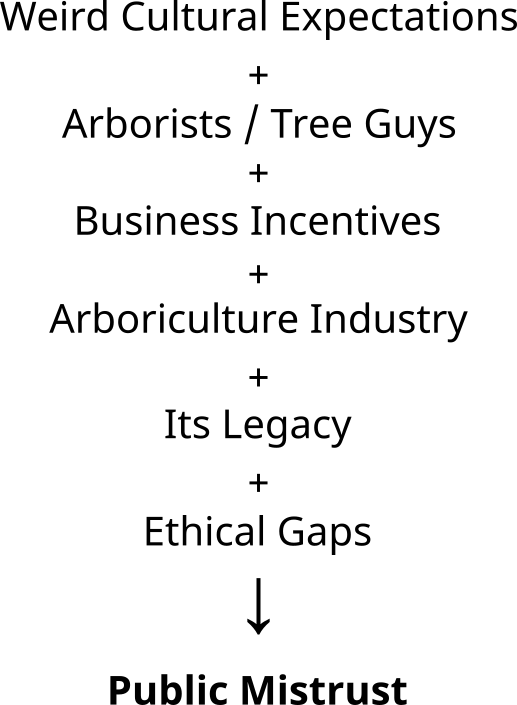

This equation is definitely more complex and more interwoven than proposed here. It is quite the exercise of restraint to not delve deeper into each of these factors, and there are certainly more of them than what I have the space for here. Each of these forces not only drives arborists and tree companies to believe the market demands tree removal, they also compound:

Weird cultural expectations + arborists + business incentives + the arboriculture industry + its legacy + ethical gaps → public mistrust of our industry.

Weird Cultural Expectations:

I think the public, this includes the arborists and tree guys, have a set of beliefs about trees that really don’t align with fundamentals of nature. We’ve an article on American culture and attitudes towards nature that explores this in-depth.

Our culture permits beauty as the primary function of trees on our properties. Referred to in some literature as ‘amenity tree care’. This is the predominant form of tree care in the United States.

This thinking is leveraged by tree care companies because they themselves have bought into these cultural dogmas. Tying together “beauty” with “healthy” and “strong” trees. Less-than-perfect trees are “unsafe” and then killed. Some tree care companies (and landscape companies too I suppose) are hired on the notion to “clean up” your property.

To keep your property free of nature, and to keep your trees less tree-like. To keep the urban forest less like a forest as they try to shape nature in their image. When those old dogmatic ideas are reinforced by those who still believe in “the way we’ve always done things”, the cycle repeats: trees removed due to very benign “defects”, trees get lion-tailed, routine insecticide sprays on every tree and shrub, excessively large removal cuts, you name it. This is a feedback loop that works in the interests of tree companies but not nature. And certainly not the public.

Once a tree looks a bit less than perfect, the non-initiated public sometimes thinks a tree is dying. Even though they’d never just kill their dog at signs of distress, they are easier to convince of this conclusion about trees because it might pose a risk to them or their home. Quite easy to spook someone in this direction, and people often are.

The public (and many tree companies too) mistakenly think tree health is a one-way street. That you can’t improve a tree’s health or its stability. That once something isn’t perfect, the only way to manage the risks is to kill it.

Take the classic “I think my tree is dying” from a potential client. Just because they think that, doesn’t mean that they want that.

Let’s say a client calls a tree company because they think their tree is dying. They’ve noticed a few large dead branches.

Arborists/Tree Guys:

The arborist or tree guy perceives this client’s certainty as wanting their tree gone. The salesperson may agree with the tree dying, whether it is or not. They may see this as a job on a platter; why should they not take it? If they don’t do it, somebody else will.

Isn’t it much easier to just agree with that client? Communicating nuance and engaging in a challenging conversation can be tiresome. It can be unrewarding, it might not lead to a sale. This representative from the tree company has incentives to take this tree down. ‘The client is afraid of it’ might be reason enough for some.

Further down the hierarchy, arborists and tree guys in the field post online bragging about how big of a “monster” they’ve killed and how quickly. When that kind of content enters mainstream algorithms, it tells the broader public exactly what we value: speed and destruction. For someone outside the trade, that’s all they see.

Of course they assume tree work is about killing trees. To be fair, for far too many arborists and tree guys, it is. We don’t take the time to show our reasoning, so they assume there isn’t any. Sometimes that assumption is right. Maybe sometimes the reasoning is that they need to make a big payment on the new shiny grapplesaw they just bought. How might the client react if we told them that?

When one company says “it has to come down” and another says “it’s fine,” they don’t see expertise. They see a guessing game. The inconsistency feels dishonest.

A lot of that comes from tree guys’ anchoring bias, “the way we’ve always done things.” We overstate risk to justify removals, assuming our understanding of stability is thorough, compounded by sales incentives.

When we advertise online, we showcase tree killing. The first images you see on pretty much any tree company’s website is their ace climber killing something. What signals are we sending? Call us out so that we can tell you to hire us to remove it?

We tree guys are conditioning the market. One client at a time. We lose the right to complain about the market demanding only removal when those are our advertisements. We lose the right to complain when we’d rather agree that a tree is dying than have a challenging conversation. That a tree can sometimes take a century to die, or that there are things that can be done to manage its condition.

We lose the right to complain when we just play on easy mode. Our decisions are clearly influenced by things other than trees.

Misalignment of Business Incentives:

Arbs need to un-industry their brain. Too many have unwavering loyalty to the dogma and paradigm of “tree work”. Working with trees can benefit trees and benefit nature. But the reality is a lot of the things we do to trees are invented to serve tree companies, to create jobs and revenue; not to benefit the environment. In many built and urban places trees are the last remnants of something real.

Many of those working in the tree industry don’t realize they work in an ecological field. There is no source instilling environmental significance into the workers. Instead, trees are over-pathologized, mistreated as decoration, and often ruined. All while disguised as tree care.

The classic Big Arb model is mostly profit-driven first, and it can be too hard for many to resist selling out trees for money. If I don’t do it, somebody else will. No aura, no stance, having lost the north star. Or perhaps never knowing where it is in the first place.

Even Alex Shigo, a tree-deity to many people, said this himself in his book 100 Tree Myths:

Many tree treatments were developed to profit the tree worker, not the tree.

The scarcity mindset held by many tree companies is quite detrimental for trees. Tree companies believe they need to be able to do any type of work that is asked of them.

As we equip ourselves for bigger and bigger work, the loans for the “necessary” equipment, the payroll for people to operate that equipment, and the expenses of running a business pile up. And so making it harder to not only care about trees, but harder to disagree with a client who thinks their tree should be removed. Tree companies think these incentives are hidden from the public. They are not.

Being overly agreeable is not truly in the spirit of ‘giving clients what they want’, another justification I hear a lot. The clients don’t know what to care about. They rely on us to inform them; for better but mostly for worse. They rely on us so-called ‘experts’ to identify and articulate what is worthwhile to think about. Just because they think the tree is going to fall doesn’t mean it will any time soon. But when we agree and comply with their fears, we reinforce their misinformed ideas about trees.

One client at a time.

Industry Organizations and Manufacturers:

The tree industry is in a unique position to affect change to public conscience because we interact with the public all the time as stewards of nature. At least, that's what we could be.

Arborist credentials are commonly treated as end-goals by tree guys. Once somebody has their ISA Certified Arborist credential, that earns them clout to the public. The CA can be used to justify pretty much anything. This isn’t a comment on the CA’s quality, it is a comment on how it is abused.

The CA may prepare some of us to make good decisions with trees, but as mentioned earlier, most arborists don’t have agency in the companies they work for to implement good practices. I certainly didn’t in the past.

The reality is that there is a spectrum of quality of those who hold the Certified Arborist credential. Not all CA’s are the same, but to the public, they are. This isn’t to say the CA is meaningless, it is to say that it is a baseline. An optional, but non-needed barrier. Plenty of arbs who are certified are shite, and plenty of them who are not certified are excellent. It isn’t necessarily a qualitative indicator to the public that ISA wants it to be. But the public thinks that it is. And that matters.

If the CA was adequate in achieving good outcomes for trees, bad practice would not be so easy to find. I’m sure any of you can walk outside into your neighborhood and find what I’m talking about without looking that hard. Many of us have killed trees that we know damn well were stable, but some credentialed-person agreed with a homeowner that it “needed to come down”.

It isn’t just industry non-profits either. Plenty of big manufacturers would qualify as ‘the industry’ here. If I were to publish this article in an industry magazine, there’d likely be an advertisement on the very next page for some big tree killin’ equipment. Wouldn’t that be funny and ironic?

The manufacturers of these machines aren’t inherently responsible for tree companies’ ongoing transformations. Though they do share some degree of culpability when their advertising is pushed onto us so aggressively. I’ll admit, I like big machines too, but it is clearly what we value more than trees. Further reinforcing to tree guys that the market demands removal, and the cycle continues as we pressure the public towards the very removals we complain about them requesting.

Legacy of Extraction:

Most people’s experience with tree guys or tree services involve tree removal, not well-articulated rationale. Not prescribed ways to reduce risk, to improve health and stress, to improve habitat quality, etc..

I live in the heart of Emerald Ash Borer country and the amount of times I have heard some version of “I was told those treatments don't work and they're just expensive” is too numerous to count. They’d rather give the client a stump than a prescription.

A stump is an easy answer, and sometimes not given out maliciously, but an answer given out of duplicity. “What if it does fail and I said it was okay?” We are asked to be experts, study what we claim to be ‘experts’ in, and give defensible opinions. At no point are we required to predict the indefinite future, or to know the unknowable. Though it'd be pretty sweet though, eh?

Perhaps there are shortcomings in tree care’s education paradigms that don’t properly prepare many arborists to actually weigh-in on a tree’s stability. Funny though, because we’re sort of expected to do that exact thing. We’re confident in saying it needs to come down, but not confident in saying that it can be left standing. A fundamental misunderstanding here of both risks and expectations.

The industry’s dominant role has been subtractive: taking trees away, getting ‘rid’ of people’s problems. After all, the default Big Arb setup is to first get some tree killin’ machines. An unfortunate magnifier of this problem is the public’s shallow tree literacy. The so-called ‘experts’ often know more about their chipper than they do about trees.

Hence why competing estimates with vastly different recommendations erode public confidence even further. One company says the tree’s gotta go, I can be here tomorrow. Another says a bit of choice end-weight reduction can meaningfully reduce the risks.

These companies could both have the same credentials, the same equipment, the same everything. How is the public to rationalize the huge variance across professional recommendations?

It is easy to come to the conclusion that tree-work is guess-work. It is easy to look at the space we’ve created and think that all we do is cut trees down.

Regulatory and Ethical Gaps:

When you look at the level of regulation, enforcement and heavy use of tree protection orders in certain European countries, you see there is a higher degree of respect and trust for arborists industry-wide than we have in the States. Here in the States, there really is no barrier of entry. Anyone and everyone can be a tree guy.

Many tree companies here allow customers to play point-and-cut, letting them dictate which tree parts are removed or which trees “need” to be killed. I’ve received that silly flyer in the mail that says “our large crew will be killing trees in your neighborhood, let us know if you need any trees killed”. This is tree work. Something that is normalized to the public. As if I, a non-educated member of the public, knows which trees need killing.

This approach, and ones like it, discredit professional arboriculture as a trade and science. Without an understanding of ecology and trees, it is inherently hard to have an ethical compass. There is a long way to go if we want to be recognized as a skilled trade.

The lack of consumer protection in our industry is quite concerning too. It is especially difficult when the non-informed are not only perpetrating the act, they’re also destroying the evidence. How can a third party check if a tree really needed to be removed if it is gone and the stump’s been removed?

What can a customer do if their tree is severely lion-tailed? Or if they discover the “PHC” company they hire sprays pesticides in ways that clearly violate laws? Sure, they can leave reviews, hire different companies, etc., but reviews won’t regrow trees.

There is recourse in some instances of egregious foul play, but oftentimes the recourse is very cost prohibitive. Not to mention, most people don’t know their legal rights, let alone want to pursue legal action in the first place.

So people get stuck with getting what they get. Oftentimes they can’t even identify what they’ve received is actually fundamentally not what they asked for.

Real Market Demands

All of these forces exacerbate and amplify each other in complicated ways. As this article was written, many connecting thoughts were omitted for the sake of brevity (not something I'm known for, I know). These things erode away at trust not just in one arborist, but in all of us. They erode and mutate our beliefs too.

Sometimes trees should come down. Though we argue, far too often are they condemned when they could be managed instead. The market demands trustworthy expertise: that’s what they think they’re getting. And by and large, this is not what they receive. We’ve taught clients to expect removals instead of advice.

Homeowners want to know what’s necessary, what’s optional, and what’s wise. They want arborists who understand risks and stability, wanting options that don’t leave them with a stump. A stump you told them was hollow without even checking. They want someone who can translate the language of trees into decisions that make sense. That demand is enormous; it's just blocked out by the noise of the chipper. The “market” only appears to demand removal because that’s the only product we’ve taught it to buy.

Arborists who consistently achieve good outcomes with both trees and clients tend to approach each interaction with the mindset that the client is seeking their expertise. Even if the client’s words don’t explicitly say it, they want guidance.

Reforming our public relationship is more worthwhile than higher productivity. If you treat every consultation as a moment of education, you’ll find that most clients are eager to learn. Interpret people’s concerns through an ecological lens, not a commercial one.

I do not think of ecocentrism as a ‘niche’ way of thinking. It is the opposite. It is the most encompassing, broadest reaching, and purposeful way to think about working with trees.

Honest and thoughtful arborists work very hard against cultural expectations about trees, against anti-tree practices and attitudes in our industry, and against silly expectations from the public.

Don’t surrender to the idea that the market demands are set in stone.

The real market demand is for intent and restraint. Values that don’t scale. But if we meet that demand, you, the reader, earn the trust that our industry squandered.

One client at a time.