Some of these things are best viewed and articulated in the video. Others are best seen in detail here in the article. The video below had a few concepts removed from it for the sake of brevity. But the video still communicates the broader concepts, whereas the article conveys more details.

I’ve had this passing curiosity about these large columns of decay I keep seeing on maple trees. A pattern that I’ve finally the time to try to figure out. I thought it would just be a Google search, checking a textbook or two. But I didn’t find a neat and simple answer that satisfied my curiosity.

Tangential decay column visible in the trunk of a red maple, Oak Park MI

And to be honest I’m still not sure if I’ve found that, because the conclusion I’m orbiting around still leaves me with lots of questions. But perhaps I’m a bit closer now.

Check out this huge decay column. Maybe you’ve seen trees before that have this feature too. To be clear, I’ve seen it on numerous other tree species too, like catalpa, linden, horse chestnut. But more often than not, when I bump into these, it is on some kind of maple tree.

Here’s what we’re going to go over in this article:

Description of the syndrome

What I don’t think causes them

What might cause them

More stuff to think about.

Description of the Syndrome

Below is a gallery of more examples of this decay feature, what we may call a ‘syndrome’ or ‘decay feature’ for now.

Maples (red, silver, freeman) mostly, but have seen this syndrome or feature on other species too. Seemingly softer-wooded species, diffuse porous species (that might be relevant later on)

Evidence of an initiating wound is absent

Tangential view of column visible

Well defined wound-margins left, right, top, but bottom is absent

Sometimes the overall shape sort of curves, usually taller than it is wide

Boundaries of the wound-wood sometimes extend into primary union

Most of the time the decay seems to extend into the root plate, lower margin of the wound is absent

Sometimes the column of decay is visible on two sides of the trunk (uncertain if they’re connected internally or not)

Have examples of them on all sides of trunk (cardinally)

No consistency of the affected trees’ health: varying degrees of dieback on some trees, other trees have normal healthy crowns

Single state of visible decay, suggesting a single causal event

Bark sometimes still attached

What I don’t think causes these

Many things can cause similar looking features on trees, both pathogenic in nature and non-pathogenic. Let’s talk about both.

Pathogenic Stuff

A large Eutypella Canker on the base of a sassafras tree in Royal Oak MI

First on the list of things that can create similar looking features on trees are cankers.

This canker has a similar shape to our syndrome-in-question. There are well-defined wound margins, but with pathogenic cankers, you can see multiple attempts from the tree to close the wound. The pathogen will kill off that living tissue, continually pushing that margin further and further outwards.

In all of the trees-in-question here, none of them have that characteristic appearance. All of the margins surrounding the large tangential decay columns in those trees are succeeding; not being killed by a pathogen.

Other cankers can create a similar shape too, such as the nectria cankers. Here is at the base of a red or black oak.

The sunken area flanked by the well-defined upper and right margins is dead tissue, despite the bark still being intact.

Nectria cankers can take many forms, and they’re typically accompanied by their classic orange fruiting bodies.

No evidence of nectria cankers have been found on the trees in question either.

As far as aggressive decaying fungi go, I don’t suspect those are causing these large features to form either.

Here is a decay-complex in the base of a bitternut tree in Southfield, Michigan. The base of this tree is colonized by both brittle cinder and armillaria. In the base of this tree, we see varying states of decomposition. The root flare on one side of the tree is totally decomposed and absent. The decay is quite advanced there, but is not as bad further up the trunk.

And again, similarly to the cankers above, these tree is showing signs of multiple attempts at initiating wound closure.

I don’t suspect what we’re observing is a heart-rot that is ‘breaking-through’ the sapwood. It is quite uncommon for heart-rotting agents to affect the sapwood; though it does happen sometimes. I think these features do not originate in the trees’ centers, but instead originates somewhere else. These old maples do lead to an interesting clue:

The shape of each of the openings into these old maples looks quite similar to our trees in question, don’t they? The upper, left, and right margins are present, and the lower margin is absent. In these old maples, you can clearly see inside the trees. I wonder if these old trees once looked like the trees-in-question? One of them even has a tangential decay column still visible.

But those decay columns have since totally decomposed. Perhaps these trees are examples of what can become of maples with this condition.

This occurs because, in this region at least, maple wood tends to decompose quite quickly. Sometimes faster than the rate they can compartmentalize their decay. So these hollows form when wound-wood has no surface area to grow upon. Ordinarily, the decayed wood in a pruning wound, for example, provides a surface upon which the new wood can close. But with decay areas that are excessively large, they’ll sometimes decompose faster than they can close over.

Non-Pathogenic Stuff

Alright, well how about other things that can cause a similarly shaped feature to form?

How about sunscald? Sunscald damage expresses as a tangential view of a decay column, right?

Sunscald example in a black oak in Hazel Park, MI

I will admit, at first I think I did write these features off as gigantic sunscald. Maples do often get scald! Except! Ordinarily we see scald high up in the tree’s crown, following either a height reduction or a naturally occurring breakage. The bark of young maple tissue is often quite thin, and sunscald will more commonly affect trees or tree tissue that has thin bark.

At the base of a maturing maple, that’s where the bark is the thickest. I would expect to see that anywhere but there, ya know? Furthermore, we have these decay columns forming on all cardinal-sides of these trunks without consistency. Sure, scald can form anywhere, but on a trunk, I’d expect more southern-facing columns for this to be the case.

The trees-in-question are often surrounded by other large trees. There’s no evidence of them being recently and drastically exposed to more sunlight.

And lastly, scald doesn’t exactly explain why these decay columns extend into the root plate.

Perhaps these large columns of decay are caused by old tear-outs? Old branch breakages?

Looking more closely at the decay column itself of the trees-in-question does not show on evidence of a tear-out or breakage. The tear-outs in the above photos are of differing states: some quite old, some only a month old. In each, different angles of torn fibers are evident. In each case, we’re looking at the middle of the column of wood, not the tangential side of it. These might qualify as ‘sagittal’ views of the wood. I’m not sure exactly, those terms sometimes confuse me lol.

Alright then, fine. How about mechanical damage to the trunk?

A few of my friends have tossed the idea out there that the trees-in-question are a result of some mechanical damage. With most severe mechanical damage, it is still evident on the decay column for some time following the damage. Of course, once things become significantly decayed, it can be much more difficult to determine.

In order above, there is some chopping damage, beaver damage, and a car strike from left to right. In each of these examples, if you look close enough, you can see the damage in the remaining column of decay.

Each of the tangential columns of decay visible on the trees-in-question lack indicators of large physical damage to them. They’re all smooth.

WELL HOW ABOUT ROOT DAMAGE?

Alright, now we’re getting warmer.

The outcomes of root damage can be quite tricky to predict. We see a large variation in the symptoms that can develop following major root damage to trees. And in some funny way, the more I practice, the less confident I feel in trying to predict what will happen.

In each of the above examples, if you would have shown me the wounds when they were freshly made, I would have cringed for the trees. Yet years on, each of these examples have healthy and normal crowns.

It is easy to say that it must be a fine thing to do then, if the trees are still in good condition. Cities are terrified of liability, and the trees get taken down quickly once and if they start showing bad enough symptoms. This means there aren’t many remaining that look bad enough, and that might wrongfully make us think most trees handle it just fine. The reality is that some can handle it just fine, and others cannot.

But check out the last two photos in the above gallery.

You see a small, but familiar shape, don’t you?

An arch on the base of that linden tree. An upper and right margin are visible, but a lower margin is absent. Attached to it is a long, damaged root that extends into the trunk.

Doesn’t that kind of look familiar? Looks like a teeny-tiny version of a nourishment blindspot.

Nourishment Blindspots (or embolism)

Back in 2022 I wrote an entire article about these. If you’re familiar with nourishment blindspots, you can skip the next section. If you want the details about them, check out the article itself.

What’s pertinent is that we define both cavitation and embolism first.

Cavitation: the moment an air bubble forms within the water column

Embolism: the condition left behind after the bubble forms

Here’s the summary of what a blindspot is, and then I’ll show some examples:

A nourishment blindspot is a region within a tree that has become physiologically isolated from effective water and nutrient transport. These zones arise when part of the tree’s internal transport system fails; most commonly through hydraulic disruption such as cavitation and embolism. The shape and extent of a nourishment blindspot are not random; they are defined by the tree’s xylem architecture.

The compartmentalization of dysfunction in trees describes both passive and active ways trees try to localize dysfunction. One of the passive ways they do that is in the xylem cells. How they grow, their size, their connectivity to each other, etc.. For the full details, again, check out that article.

Nourishment blindspots, or embolisms, that form following pruning illustrate something quite cool. They illustrate how the xylem beneath the wound ‘supplied’ water to the now-removed stem.

A diagram I made to illustrate why the blindspot cavitates backwards

In the water’s path above, the xylem cavitate back to a point where they are integrated with adjacent pathways. The ones that dry out are not connected to anything else, and so that is why they decay just like the wound does. The full article on nourishment blindspots shows how this looks at the cellular level.

There is certainly a relationship between the size of the cut and the size of the blindspot, or embolism. A larger cut tends to create a larger blindspot when they do indeed form. And that is of consequence to the tree because it makes for a much larger wound.

How does this connect to the syndrome we’re looking at?

When we’re looking at the trees-in-question and nourishment blindspots from pruning, we see a large tangential column of decay, right? We’re looking at the side of the column.

But the syndrome we’re looking at tends to lack an obvious wound. Importantly here, cavitation (and subsequent embolism) can occur even without a wound.

We’re going on a tangent ourselves here briefly:

Droughts can cause them. Severe soil compaction could cause them too. Anything that might stop a root from absorbing water can cause a cavitation. Freezing too, actually.

Whenever the water column is stretched super thin it can sort of ‘snap’, and embolism can expand. Cavitation occurs first, the margins of which are largely defined by the passive CODIT structures (the hydraulic architecture). The decay is a result of the embolism. The tree usually relies on the physical characteristics of the xylem cells first. Since trees are slow, if something is stationary and already in place to act defensively, it is sort of the first line of defense before they can have an ‘active’ response.

But there is no ‘active response’ if those pathways are hydraulically dysfunctional lol.

Trees all handle this differently. Some trees have a great capacity to deal with cavitation. Some don’t. There’s a spectrum.

Some trees could be described as having a hydraulic architecture as being ‘sectorial’. The xylem tend to form independent ‘sectors’ or ‘territories’ with limited crossover to other sectors. At the other end of the spectrum a tree that has a lot of crossover might be said to have a more ‘integrated’ hydraulic architecture.

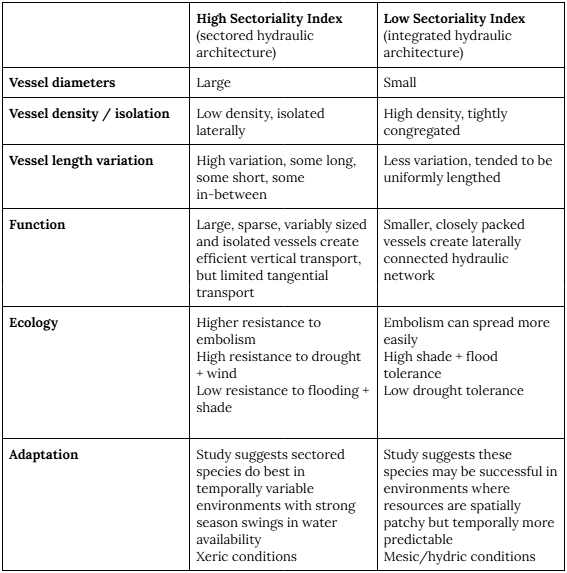

Below is a chart that is a good primer on sectorialism in trees:

A chart I made using information from this study, also cited in the sources section at the end of this article

Generally trees that are highly sectored do a good job of keeping dysfunction ‘contained’ within that sector. Whereas trees with a highly integrated hydraulic architecture tend to not be as good at that. And of course, like all things, there’s a spectrum here. There is variation across not only species, but of individuals in the same species across different biomes too. Predictability is quite hard here, but there are some obvious standouts:

Bristlecone pine is one of the champions of sectorialism, characterized by the obvious single vertical ‘bark strips’ they have keeping them alive, resting on dead tissue.

Could what we’re seeing be sectorialism on maples?

Based on the chart above, maples don’t really have any of the characteristics of trees thought of as being highly sectored. They tend to live in mesic environments, their wood is diffusely porous, are intolerant to drought; pretty much are firmly in the low in every category of the sectoriality index.

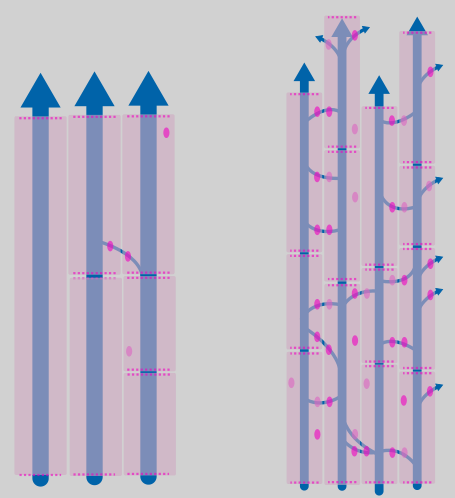

But we’re getting warmer. Let me show you some diagrams; I know they’re kind of crude lol. This section might be better illustrated in the YouTube video:

Very crude and simplified concepts of trees that are highly sectored (left) and integrated (right)

The tree on the left is high on the sectoriality index. Each hydraulic ‘sector’ is sort of independent of one another and never merge together. The tree on the left is low on the sectoriality index.

Cells I illustrated to conceptualize hydraulic architecture. On the left, highly sectored architecture. On the right, highly integrated architecture.

It is reasonable to posit that roots are all sort of autonomous from one another, right? One major root doesn’t have much interaction with another on the opposite side of the trunk. To this end, you might say each root is ‘sectored’, or rather, it supplies its own ‘territory’ until they merge together at the base of the tree, denoted by the circle in the right image. Beyond that circle, there is significant integration with all of the other territories or sectors.

The hydraulic architecture beyond that circle has more connections create more tangential water pathways, connecting them to their neighbors to their left and right. They become more integrated beyond that point, helping water absorbed by one root ‘supply’ other areas of the crown, not just the branches directly above it.

And the height of this circle varies. Where the roots truly integrate with each other is anyone’s guess. I suppose all trees have this circle somewhere, right? Regardless of if they’re highly sectored or highly integrated.

What Might Cause Them

This part might also be best explained in the video. Here goes:

Let’s say a root dies. Regardless of the cause, it can no longer take up water. Total dysfunction.

As the tree photosynthesizes, evapotranspiration and internal pressure pulls the remaining water out of the territory.

A GIF from the YouTube video illustrating the territory being dried out, leaving behind a large embolism following root dysfunction.

That water cannot be refilled. That territory empties, leaving a huge embolism. Leaving this large tangential column, just like the pruning nourishment blindspot, but without a wound.

The resulting embolized column would extend upward through the portion of the stem hydraulically connected to that root, effectively deactivating that internal volume of wood. The clear boundaries might show the natural limits of flow integration between root-derived territories, even in species that are not anatomically “sectorial” in the classical sense. Potential evidence of how a root-origin embolism can shape decay patterns within the trunk. To reference the sectorial illustrations above, the circle might represent where the upper margins might be.

Once that happens, the area becomes susceptible to the other regular ‘decay’ processes we think of.

In less words:

Cavitation is triggered in the root

Runaway embolism collapses conductance of the entire territory up to the location where it integrates with adjacent territories

Tissue becomes hydraulically dysfunctional, dries out, metabolically isolated, forming a nourishment blindspot

Decay initiates within the territory

It is pretty well-accepted that branches die as a result of root damage or major soil disturbance, right?

Each of these trees has some known root/soil disturbance that is causing the crown to have some dysfunction.

But we also consistently see trees that have root/soil disturbance that show pretty much no symptom development too. Suggesting a spectrum of possible outcomes to this kind of damage.

Perhaps it is not unreasonable to add this tangential column of decay we’re seeing in maples to that spectrum of possible outcomes. Almost an in-between of the two extremes.

As a reminder, the health of the trees-in-question vary. Some are totally normally looking, and others not-so-much.

I didn’t realize until well-into making this article and video that there are a number of trees on streets and sidewalks that do have the tangential column of decay visible. Trees on streets and sidewalks often receive root damage, and again, have varying responses to that. And perhaps these tangential columns should be added to that spectrum.

Earlier I showed images of damage that was well-contained on damaged roots, but above we see perhaps those vascular territories collapsing and embolizing after being damaged.

Re-examining the old hollow maple trees shown earlier, the ones the lack the lower margin entirely, further reinforces this as a possibility to me.

More Questions

Maybe I’m way off, maybe I’m missing something very obvious. Might be too in the weeds. Maybe I’m going the long way around something already well-known and I didn’t get the memo lol.

But believe me, I’ve got questions here.

Chief among them though, what really determines the maximum height of these embolisms? Is it really where the other root ‘territories’ combine and merge together?

How else might these big embolisms connect to sectorialism? And does sectorialism neatly explain the phenomenon?

Is there some consistent type of root-death or root-dysfunction that predisposes trees to forming these huge embolisms?

Does the plant’s health affect the size of the cavitation?

Why don’t we see more of these? (Or maybe we do, and we just don’t realize it)

I’ll probably add more questions as time goes on. Or perhaps, remove some. But for now, I am glad to get this concept out there and out of my mind. It has been a back-burner project since the middle of the year, and I’m happy to not think about it for a little while.

I do feel more satisfied having tried to figure it out, even if I do still have lots of questions.

If you’ve made it this far, as always, thank you very much.