This article takes a close look at the commonly held notion that removing deadwood from trees improves their health.

This is a technical article written for practicing arborists and students of arboriculture.

This article also appeared in two parts in the February 2021 and April 2021 issues of the Tree Care Industry Association Magazine.

Last December, Jack and I pruned some hazardous deadwood for a client over her garage from a large northern red oak. She was primarily concerned with not having another hole in the roof of the garage from failing deadwood.

The customer had told us a tree service condemned the tree. The salesperson took one glance at the tree and exclaimed it had to come down. A tree of this size is not a cheap removal. It is a little embarrassing that there are salespeople in arboriculture that actually leverage fear as a selling technique.

After a brief inspection, I didn’t see a single thing that justified immediate removal. The tree was not in tip-top shape, but it didn’t show any significant defects from any viewpoint on the ground, let alone the single position this salesperson saw the tree.

A large, woody vine grew up up the side of the trunk that had been severed at its base years ago. The vine was dead but still on the tree. It looked a little ragged, but it was not impacting the tree's health whatsoever. There were several large dead branches in the tree's crown, which corresponded to a driveway installed on its roots about 15 years prior.

The soil level was high surrounding the trunk, too, but these are all normal things that happen to trees in urban areas.

The customer was interested in keeping her garage roof damage-free, so that's what we addressed; we reduced the length of the dead branches to a safe size. After we finished our pruning, said our goodbyes, I emailed our customer her receipt. When she replied, she said she was grateful that we "gave her tree a second chance at life."

The sentiment was nice, but that isn't at all what we did. All we did was reduce the residual risk of the tree and made it safer to be around. The customer was actually grateful that our professional opinion was contradictory to a lame salesperson, and perhaps that's what "saved the tree." If I were to address the tree's health, I would tend to the soil issues first and foremost.

So that got me wondering: Do people really think removing deadwood improves the health of a tree?

Yes. Yes, they do.

That's what tree companies tell homeowners, and it's an easy and intuitive thing to sell. It is part of the old dogma of tree work, along with the long list of other needless things sold to people for their trees (e.g., topping, thinning, excessively large pruning, etc.)

I began phishing through my textbooks and online studies with intent:

Does removing deadwood actually improve the health of a tree?

What I found is complicated

From ISA podcasts to Dujesiefken’s Lifespan Approach, or in TreeBuzz forums, everybody refers to deadwood as simply “deadwood”. It seems like nobody looks further than that. In this article, I look into the ways branches die, how the tree copes with dead branches, and if removing those parts truly improves the health of a tree.

Each of the processes discussed from hereon is of healthy, functioning plants. These processes can fail, but they are described as if they are functioning optimally. These processes may not work correctly in a low energy state, weakened, or diseased tree.

SECTION 1

Abscission

We’re familiar with leaf abscission in autumn, but the process is the same when it comes to cladoptosis (which is the natural shedding of branches), just at a larger scale (Bhat et al.) (Hirons). From here on out, I will use the terms abscission and cladoptosis interchangeably for the sake of clarity. They essentially mean the same thing in the context of this article because we’re talking about tree crowns, not tree leaves.

The tree will shed particular branches when it costs too much to keep those parts alive; those parts use more photosynthates than they produce (Bhat et al.) (Bellani et al.). In essence, trees are often modular in this way. It is also theorized that trees will undergo cladoptosis in response to drought, to reduce the surface area where water can be lost (Bhat et al.)(Hirons).

The plant detects the dysfunctional branch, and the process of cladoptosis begins—it is a function of the plant to do this. The catalyst of cladoptosis is usually abiotic, not pathogens (although sometimes they are the catalyst). Excessive shading or inefficient photosynthesis, retrenchment, or the expected loss of crown mass following root mass severance can trigger branch abscission (Addicott) (Hirons) (Pallardy). Dysfunctional branches become biologically separated from the tree, and although they may physically be attached (Bellani et al).

Generally speaking, abscised branches are found in the interior and lower parts of a tree’s crown (Bellani et al.). My anecdotal experience also supports this observation, and I’m sure most arborists can agree with this, too. For example, here in Michigan, perfectly healthy Norway maple trees (Acer platanoides) regularly shed interior branches. Honeylocust (Gleditsia triacanthos) shares the same habit, sometimes abscising large branches, almost lion-tailing themselves.

Further Notes on Abscission

In Dujesiefken’s Lifespan Approach, in a section about cladoptosis, he refers to a predetermined breaking point caused by fungi. He goes on to say “The decay does not usually penetrate through the boundary layer into the stem, as a result of this process, known in forestry terms as ‘self-pruning.’”

He attributes this predetermined breaking location to the fungi. Contrary to his statement, both Bhat and Bellani’s studies show this is caused by the tree itself: the abscission zone. It may be more accurate to say saprophytes will break down the wood near the abscission zone, which accelerates detachment of the part.

The abscission process goes through recognizable phases (Addicott). I’m going to highlight the abscission zone because it is the primary part of the abscission process that prevents decay ingress into the main stem.

Abscission Zone

In branches that the tree abscises, a cellular layer called the abscission zone forms. This is where things get interesting, and a stark difference from CODIT becomes clearer.

Within the abscission zone, there is a region of cells (the separation zone) that do not contain lignin (Bhat et al.), which the saprophytic fungi would ordinarily consume (“Saprophytic Fungi”). This zone functions like a gap that makes it more difficult for potentially opportunistic fungi to enter the living part of the tree while the branch is attached (Bhat et al.). Outside of this zone is a layer of cells packed with suberin and lignin, which serve as additional protection from pathogens once the limb has detached (Addicott) (Bhat et al.) (Stern).

The construction of the abscission zone prevents decay ingress while the branch is attached and while the branch is detached from the tree.

Abscission compared to CODIT

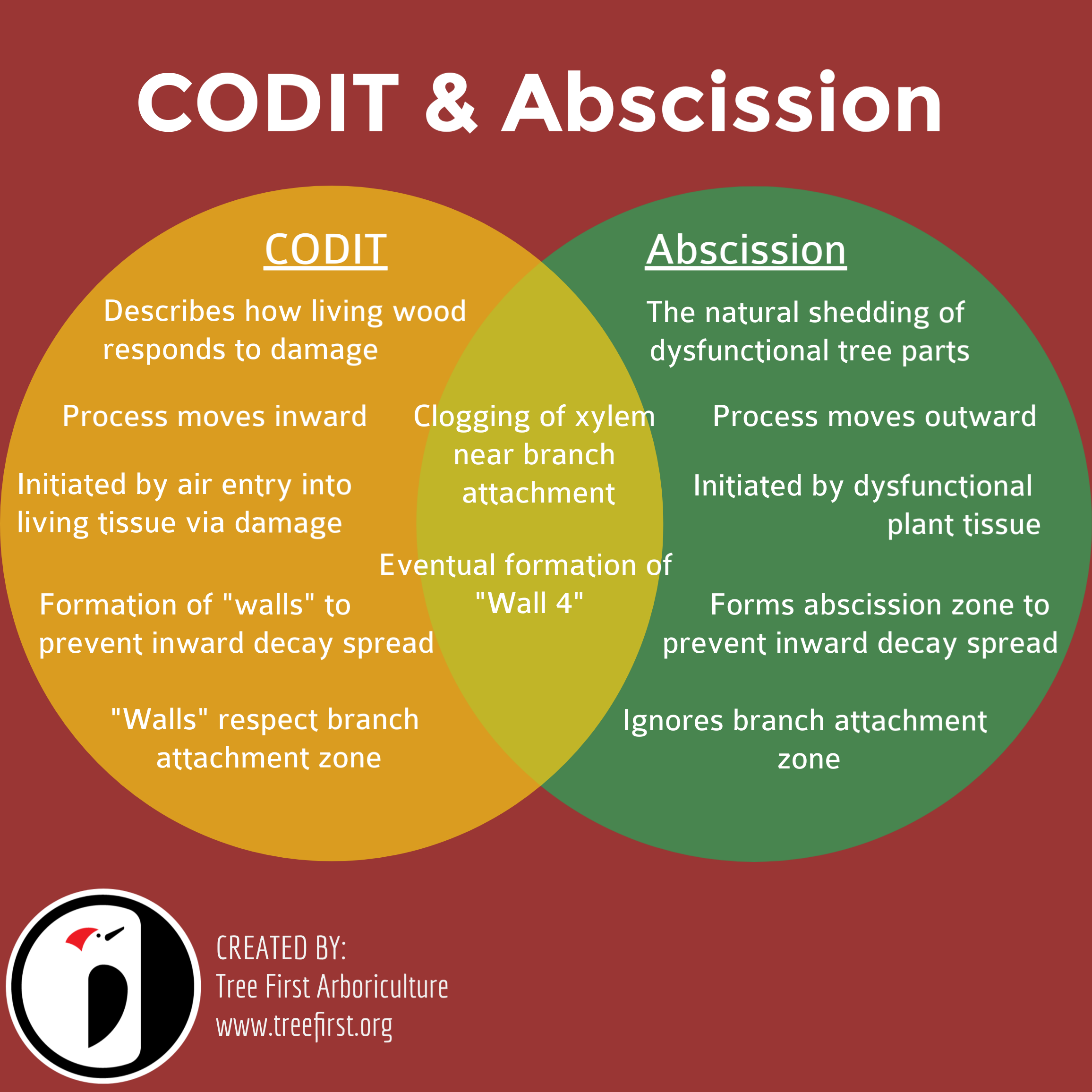

Both abscission and CODIT have functions to stop the spread of decay into the main stem, albeit in slightly differing ways.

When talking pruning practices, the application of CODIT in trees to cutting live wood is well supported and applicable (Shigo et al.). CODIT, however, does not fully explain the processes involved with the tree shedding branches on its own with no apparent wounding (Gilman). It is a different process, though it does share some overlap with abscission, which I will illustrate in the comparison section below (Dujesiefken et al.).

Here, I want to review the similarities and differences between branches killed by wounding/pathogen entry and branches killed by abscission.

Similarities

In abscised branches, the tree—at least in some cases—will clog the xylem with tyloses or gums or resins above the abscised branch to prevent vertical spread of decay (Bhat) (Hirons) .

Bhat’s abscission study writes:

...the rays at this level of the branchlet, and slightly above, where the mechanical rupture occurs show dense accumulation of dark brown contents… Substances such as polyphenols, tannins and resins, often found deposited within xylem tissue, are generally believed to serve a protective function owing to their toxic or repellent properties.

Bhat here is describing how “Wall 1” functions in the CODIT model (Gilman). This is a shared characteristic between abscission and the CODIT model. Secondary growth, or basically trunk expansion, will eventually form distinctive trunk collars on limbs dead from both abscission and other means. A “wall 4” will eventually be present on both wounds and normal abscission, though the abscission zone doesn’t depend on the presence of this fourth wall to protect the stem.

Differences

The placement of the abscission zone and the placement of the internal walls of CODIT differ—that is, the placement of their major mechanisms of preventing decay entry.

“Wall 2” exists only to prevent the inward spread of decaying organisms to the main stem. Its strength relies on the difficulty organisms have when passing through the distinct layers of growth rings (Gilman). As we’ve learned CODIT’s functions, we’re to ensure our cuts are as close to the branch collar as they can be to expedite wound closure (Gilman).

When it comes to cladoptosis, the abscission zone, on the other hand, is what prevents inward spread of decaying organisms. Very interestingly, the abscission zone seems to ignore the branch attachment zone, as shown here below.

from A Lifespan Approach, Dujesiefken, Fay, de Groot, de Berker

The tissue behind the abscission zone shows slight discoloration. But the branch attachment zone itself remains the same color as the surrounding trunk tissue, which leads me to determine that tissue is unaffected by decay. The branch shows expected discoloration as the stem dries, and the decay process continues therein.

On a branch removed in pruning, close to the collar, the CODIT walls behave with more obedience to the branch attachment zone.

from A Lifespan Approach, Dujesiefken, Fay, de Groot, de Berker

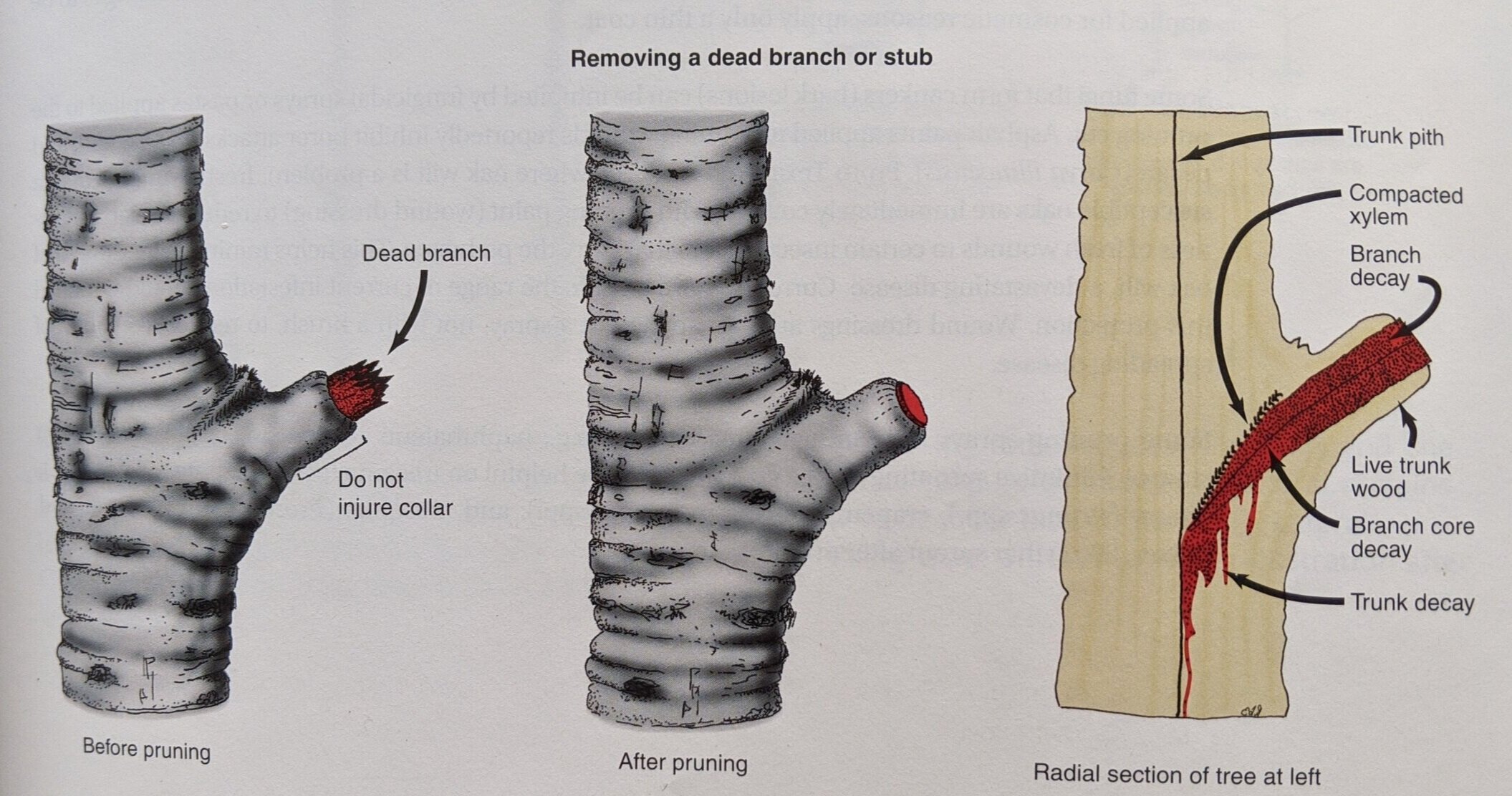

Once we cause damage to the tree, the remaining bit of branch will decay into that branch attachment zone (Dujesiefken et al) (Gilman). Ideally the process of wound closure secludes that small decay pocket, creating an airless space where fungi cannot continue to decay into the tree. The decaying organisms are allowed closer to the main stem when we cut live wood (CODIT) than when the tree kills branches on its own (cladoptosis).

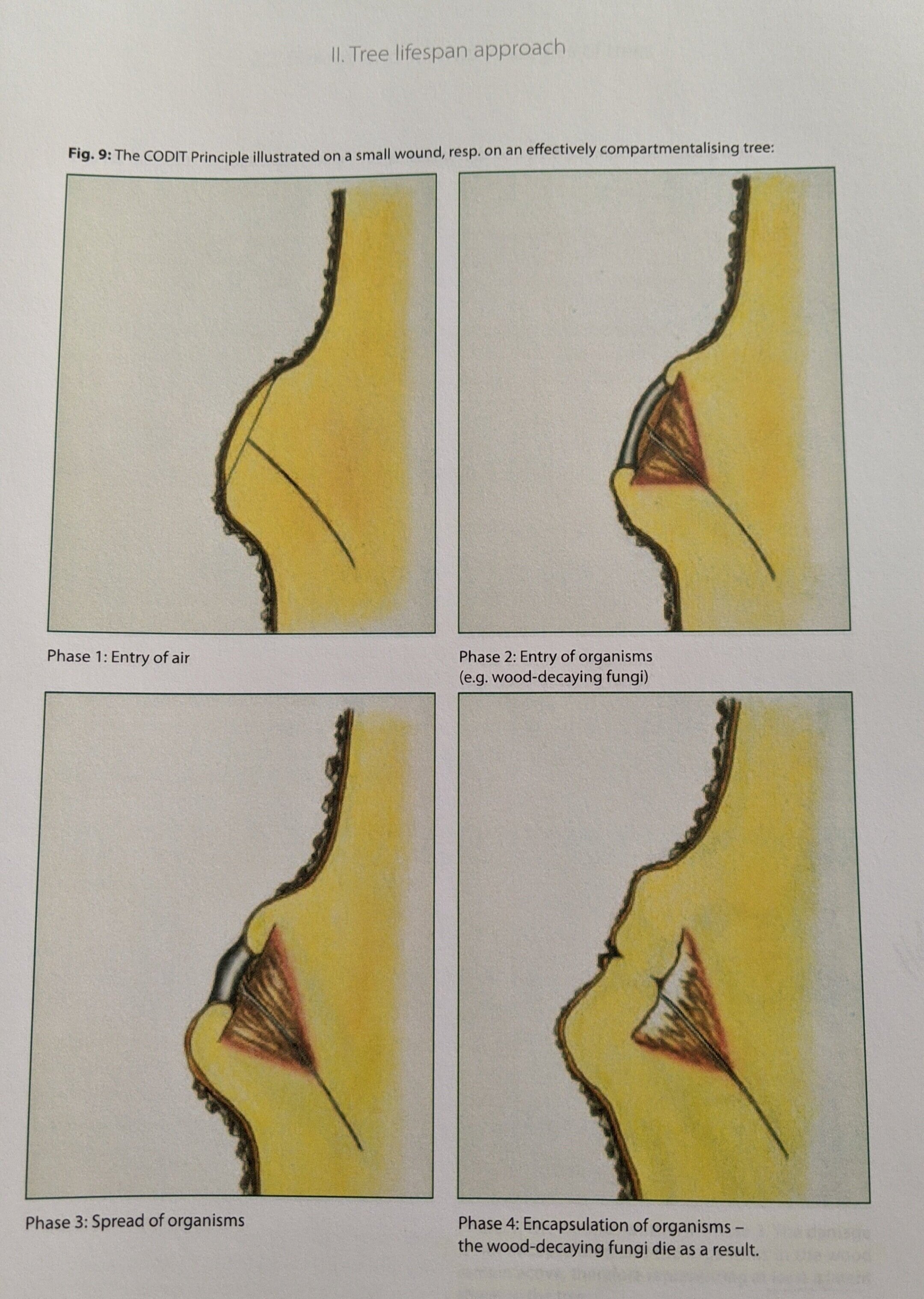

CODIT describes how the tree will respond to air entry into wounds on live tissue, such as pruning or a breakage (Dujesiefken et al.). This is a fundamental difference between a branch killed by abscission and branch killed by a poor pruning cut—the entry of air into living tree tissue initiates the CODIT process. In contrast, in abscission, there is no air entry into living tissue at all (Dujesiefken et al.).

Dujesiefken explicitly says decay does not usually penetrate through the boundary layer into the main stem in abscised branches. There is no air inside behind the abscission layer if it is healthy. Decaying organisms need oxygen to survive. And without that, decay can’t happen.

The diagram below best sums up the similarities and differences between the processes trees undergo to deal with damage to living wood and how trees shed its own branches.

Section 2

Why compare Abscission with CODIT?

When comparing abscission to CODIT, it seems like I’m comparing two different things. One function describes how trees kill their own limbs. The other explains what happens when healthy tree tissue is damaged. They’re two different things, right? Yes.

I compared these two plant functions because they both have mechanisms to prevent decay ingress into the tree. Removing dead abscised limbs from trees under the notion that the tree needs to compartmentalize over the deadwood to protect itself isn’t necessarily true. Applying the CODIT principles of wound closure to branches that were abscised, doesn’t hold up because the mechanisms in place do not depend on wound closure.

As explained in the above section, the mechanisms the tree has in place to protect itself are different when the tree itself has killed off its branches, versus when an outside source causes damage to live tissue

It would seem here then, establishing how a branch has died is important in determining if removing it would have a positive impact on the tree. If the cause of death can be reasonably determined, you know what mechanisms are in place. Pruning abscised branches probably does not improve the overall health of the tree. But if the branch died from other means, like, a bad pruning cut, the course of action may be different because air has entered the living branch.

There are a few ways to tell the difference between dead abscised branches and dead non-abscised branches. There are many variables involved, but these three simple descriptions are worth noting.

1. Abscised

Abscised branches are likely to be whole, with all of their large architecture intact; the small branches and twigs would fall off more easily over time. You likely won’t see old cuts on abscised branches. If you see breakages with no response wood, that limb could have broken after it abscised.

The presence of saprophytic fungi species on a dead branch with no apparent wounding could be considered benign. Granted, it is possible to have many species of fungi colonizing a single piece of wood. Regardless, in a healthy tree, the mechanisms in place should keep the main stem protected.

2. Non-abscised

Dead branches with an obvious pruning cut heading them off probably didn’t die from abscission. The same could be said about a dead broken branch that shows response growth. In either case, that type of damage serves as an entry point for decaying organisms.

If you can positively identify pathogenic fungi on a dead branch with the presence of a mushroom, removing this branch would be beneficial because it, at least, poses a latent threat to the tree should it be in a low energy state (Dujesiefken).

3. Location

Determining the cause of deadwood can also be aided by the branch’s location—where in the crown is it? Generally, abscised branches are in the lower and interior part of the crown, where non-abscised limbs can be seen anywhere in the crown.

So what if the crown has large dead on the top? It presumably isn’t abscission, and it may be more reasonable here to assume something more serious is happening. Have the tree’s roots recently (recent in terms of tree-time) been severed? What’s the tree species? Could it be bark beetles?

If there are dead lower branches with no apparent wounding, with other noticeable defects around the limb, it may not be abscission—for example, a dead limb with an entire decay column visible beneath likely doesn’t qualify as abscission.

Section 3

Arguments for removing deadwood

Now, I want to address the common notion some arborists use in support of removing deadwood from trees to improve their health.

The Common Argument

The common argument that deadwood removal benefits the tree is such: Removing deadwood benefits the tree because it allows the tree to close over wounds faster. This position was made frequently by those in the deadwood thread on Tree Buzz, and those mostly relied on anecdotal evidence.

The argument has an issue in its design, in that it does not acknowledge a difference in the ways branches die, ergo the mechanisms in place. It lumps all deadwood together. An abscised branch has no wound to close, where a non-abscised, damaged branch does. Generally, the only wounds that need closing are the ones made by making cuts on live tissue.

I found the image below in Gilman’s Illustrated Guide to Pruning. Given the way the image is illustrated, removing stub would benefit the overall tree.

from An Illustrated Guide to Pruning, Gilman

For this image to be true though, that dead branch would have likely either received a heading cut or broke off while living, both of which would have allowed air entry into branch when it was alive. The tree pictured is either a poor compartmentalizer or has a low-energy state. This image does not describe an abscised branch, for abscised branches do not depend on wound closure to protect the main stem to which they’re attached, as described in Section 1. Their abscission layer prevents decay ingress while the dead branch is attached to the tree, and once the limb falls off.

In ISA’s Science of Arboriculture Podcast, episode What Does Science Say about Pruning Mature Trees, speaker Linda Chalker-Scott gives a very compelling lecture. In her discussion about pruning, Chalker-Scott talks about the avoidance of leaving stubs. She does not specify either live or dead stubs. The speaker also does not go into detail about why one should remove stubs. I think she’s talking specifically when we prune live material on mature trees; not leaving living stubs.

Linda Chalker-Scott here is properly applying CODIT’s principles. She’s emphasizing by leaving living stubs, we’re making the compartmentalization process take longer when cutting live tissue. I do not disagree with her on that. I think though, it could be specified she’s not talking about abscised dead branches.

It is also possible her reasoning could be categorized in what’s called the Sugar Stick Theory (Dujesiefken); the more common argument supporting removing deadwood.

The Sugar Stick Theory

The deadwood thread on Tree Buzz I mentioned earlier is fascinating. The discussion began back in 2008 and is still ongoing. The basis of the debate is the same premise as this article: does removing deadwood actually help a tree? Many arborists in the thread claim that retaining deadwood means retaining a food source for pathogens.

The decaying organisms which consume the already deadwood are not inherently pathogenic. Pathogens target living wood. Not all fungi are pathogenic, and most are saprophytic (“Saprophytic Fungi”). Extremely virulent pathogens exist, but they’re few and far between.

A breach by opportunistic fungi is a failure on the tree’s part. What puts the fungi in a position to succeed is the tree’s low-energy state, not an abundance of “food.” The “food source” of a pathogenic fungi would be living tissue. Dead pieces are biologically separated, or in the process thereof, from the tree, remember?

We understand opportunistic fungi can break through the defenses of stressed, low-energy plants. The removal-of-food-source concept applied to non-abscised deadwood doesn’t remove the food source for fungi because the branch has decayed into the branch attachment. It accelerates the compartmentalization process, but it doesn’t entirely remove the food source.

All of the outlined mechanisms trees utilize to prevent decay function optimally when the tree is not stressed, or in a high-energy state. Does removing the “food source” for fungi impact the tree’s energy state? No it doesn’t.

To address that, it is more worthwhile to address the tree health in the soil, rather than pruning.

Section 4

My Speculation

By removing deadwood of any kind, we’re addressing a symptom, not the cause. Wood dies in a number of ways; abscission, damage, retrenchment, insects, etc. In any case, removing the dead material does not address the cause. I don’t think removing deadwood directly improves the health of a tree.

Abscised branches do not depend on wound closure to protect the main stem they’re attached to, so to me, it does not stand to reason that removing that type of deadwood improves tree health. In very unhealthy trees, the removal of non-abscised dead branches in tandem with real health improvement procedures may have a small and indirect benefit.

Should the tree be in a healthy energy state, it seems we’re comfortable relying on its defense mechanisms. We should be striving to improve a tree’s health then. There are many well-supported procedures we could perform on trees if health were our actual concern.

Contrary to Gilman’s image in the above section, Dujesiefken states, “The only purpose of deadwood removal is to keep trees in a safe condition.” Notice the use of the explicative “only.”

Don’t get me wrong; I love climbing and chasing deadwood out of tree crowns though I dispute the claim that it makes any direct impact on tree health. If I could find a way to justify it as wholly beneficial, I would. I’m not arguing against removing hazardous deadwood or improving aesthetics. It must be said, too, a vast majority of trees do not get their deadwood manually removed by an arborist. The mechanisms they have in place are generally effective.

It is particularly challenging in this subject to point at things concretely because of the time it takes to study trees, and because of the incredibly high number of variables involved in tree systems. One major question stands out: what metric would we even use to measure to determine if removing deadwood made a positive impact? Each thing I can think of is a combination of factors, such as growth rate or decline rate--how could we narrow down the influence of a single factor? I’m not entirely sure how we could quantifiably determine if removing deadwood directly benefits the tree.

Section 5

Implications and Questions

This section contains some questions that come to my mind after reading a lot about this subject.

I wonder, could a bad pruning cut initiate an abscission response? I’ve seen small branches killed by heading cuts. The tree detects the dysfunction (ie loss of leaves and disrupted auxin levels), and begins to abscise the branch?

In Pallardy’s textbook The Physiology of Woody Plants, he and the other authors say abscised branches may or may not have an abscission zone. Clarity on this note would be helpful.

I’d like to do more wood dissections on branch attachment zones of non-abscised dead branches and abscised branches. Seeing inside will further develop my opinion on this subject. If anyone has any before-and-after images of dissections they’ve done, I’m interested in seeing those.

A comparison involving the use of either a resistograph or tomograph would be insightful; to get a closer look at these defense mechanisms. I am interested in comparing tomographic images of un-closed wounds made on live tissue with tomographic images of similar-sized abscised branches of the same species.

Two of the works cited here mention plant part senescence. While trying to find a difference between abscission and senescence, I found very muddy explanations. Some resources I skimmed even lump the two together.

In short, it is my understanding that senescence is a product of age that, in some cases, could be called natural crown retrenchment. In other cases senescence was summed up in casual reading as “plant parts die when they get old”. I didn’t look very far into this because this phenomenon has less recognizable patterns than other common tree processes.

It is possible, had I looked more deeply into senescence, it could have been relevant to this article. If you have any insight on this, let me know.

Final Acknowledgement

Certain subjects don’t get reassessed once the community has agreed on it--such as the nature of deadwood. Do people think removing deadwood is beneficial to a tree’s health? Yes, they do! Both arborists and homeowners seem to believe that. This article has laid out why would be disingenuous to claim that removing deadwood directly improves the health of a tree, though it may—in some cases—have a small and indirect benefit. Removing stems infected with sooty bark disease or fire blight are examples where it is likely helpful, but these are not common across all trees.

In my experience, the arboriculture industry here in the States could be a more ethical and honest one when it comes to interacting and selling with homeowners. The use of explicit language in any profession is what protects us and educates others. Pruning deadwood is for safety, and selling it as improving a tree’s health would be disingenuous.

Bob Wulkowicz (RIP), a profoundly thoughtful arborist, said in the deadwood thread on Tree Buzz:

Chainsaws and bucket trucks changed this industry significantly and we need to recognize (admit) that legacy. On one hand, we had greater access and increased efficiencies in the removal of limbs and wood. We also set the scene for increased profits and steady employment. Those are realities, but there is an inherent slippery slope of replacing conscious tree care with how much wood is put in the chipper.

Larger organizations in the arboriculture community inadvertently perpetuate the poor science by presenting information as finite rather than part of an evolving science. Smaller companies and arborists get their information from them, and then it gets sold to homeowners. The extensive and frivolous pruning the residential arboriculture industry sells in the name of tree health is absurd, even if it is genuine and innocent ignorance.

Wulkowicz also says in the forum:

We should also remember the deadwood fills our gas tanks and pays our mortgages so there are powerful forces aligned to defend and encourage deadwood removal. The important thing is to try to maintain some sort of perspective that recognizes the truths of both biology and economics.

He’s exactly right: “Big Arb” is a large body that can’t pivot nimbly, no big industry can. It can’t very well say “removing deadwood is pretty benign” because that is how a lot of us make our living. Arborists have a duty to not take advantage of the resilience of trees, and likewise, a duty to not take advantage of people’s ignorance. If small companies themselves think deadwood removal benefits a tree’s health, that makes it easier for them to sell it to homeowners.

I'm not saying people are intentionally misled (though sometimes that is the case); certain things just don't get carefully examined because some decision has already been made. My thoughts about this are best summed up by Wulkowicz, again:

...all that one had to do to justify pruning was to waive a page with the printed reasons of "Why we prune". Now a number of those pronouncements are simply embarrassing. Those dogmas and then reconsiderations are always likely to be a part of evolving science. It is also interesting that an awful lot of people think that those facts are at the end of finite knowledge and anything "further" is irrelevant or irritating.

Reassessing commonly held beliefs and standards is vital to all of us as students of arboriculture, it’s how we’re all going to improve. Removing deadwood may not be detrimental to the tree, but that doesn’t inherently mean it is beneficial. Do not forget, as arborists, we’re supposed to be helping trees. Tree First.

Thank you for reading.

Works Cited

Addicott, Fredrick T. Abscission. Univ. of California Press, 1982.

Bellani, Lorenzam., and Alessandro Bottacci. “Anatomical Studies of Branchlet Abscission Related to Crown Modification in Quercus Cerris L.” Trees, vol. 10, no. 1, 1995, doi:10.1007/bf00197775.

Bhat, K. V., et al. “Anatomy Of Branch Abscission In Lagerstroemia Microcarpa Wight.” New Phytologist, vol. 103, no. 1, 1986, pp. 177–183., doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1986.tb00606.x.

Chalker-Scott, Linda. “Science of Arboriculture Podcast.” What Does Science Say about Pruning Mature Trees? Oct. 20, 2017

“deadwood.” The BuzzBoard, www.treebuzz.com/forum/threads/dead-wood.9435/.

Dujesiefken, Dirk, et al. Trees - a Lifespan Approach Contributions to Arboriculture from European Practitioners. Fundacja EkoRozwoju, 2016.

Gilman, Edward F. An Illustrated Guide to Pruning. Delmar, 2012.

Hirons, Andrew D., and Peter Thomas. Applied Tree Biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2018.

Pallardy, Stephen G., and T. T. Kozlowski. Physiology of Woody Plants. Elsevier, 2007.

“Saprophytic Fungi.” Saprophytic Fungi, fungimap.org.au/about-fungi/saprophytic-fungi

Shigo, Alex L., et al. Compartmentalization of Decay in Trees. Forest Service, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, 1977.

Stern, Kingsley R., and James E. Bidlack. Introductory Plant Biology. McGraw-Hill, 2008.